21 Min Read

Donor Psychology 101: The Science Behind Why People Donate

Table of Content

Download Paymattic – it’s Free!

Subscribe To Get

WordPress Guides, Tips, and Tutorials

We will never spam you. We will only send you product updates and tips.

A research article published in the PLOS One journal showed that, in donor psychology, giving is driven by two big factors: ease and identity.

This study shows that people are most likely to donate when they feel the process is simple and when giving aligns with their “moral compass.” While social pressure works well for public acts like volunteering, private acts like donating blood or money are driven by internal values.

The research proves that for a donor to move from “wanting to help” to “actually giving,” they must feel both morally obligated and practically capable of completing the task quickly.

Interesting, right?

Psychological factors motivate, demotivate, and push your donors in multiple directions. If you know how donors think or act, you can steer the ship towards your nonprofit more effectively.

Today, we are going to dismantle donor psychology. We’ll look at the geometry of donor psychology, psychological factors behind donating to charity, and how to encourage more people to donate.

And I’ll suggest you open your notepad and take notes.

So, let’s get started.

Why donor psychology?

Donors are human. Before asking for money, you need to understand people, especially when there is no direct benefit for them.

Let’s look at one theory that’ll help you understand your donors.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

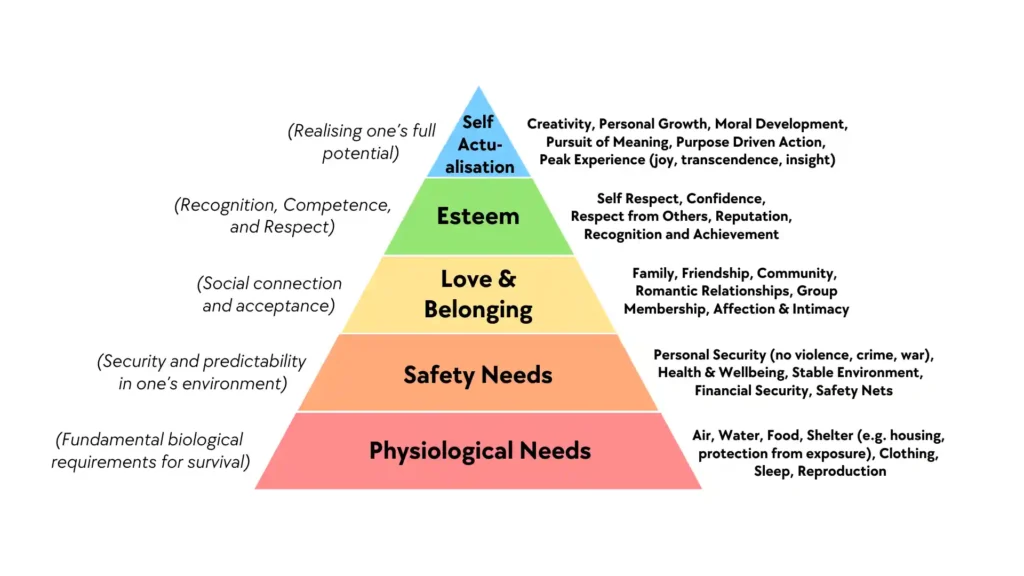

In 1943, American psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed a framework of human needs. It’s called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. And it’s one of the most striking contributions in human psychology.

In his hierarchy, Maslow said that human contribution depends on the needs they have to meet.

Think of it like a pyramid. The bottom needs are the most important ones. And the top layer is only touched after its needs below are fulfilled.

The stages are (from the top of the pyramid):

- Physiological needs (survival)

- Safety needs (security)

- Love and belonging (social needs)

- Esteem (respect and achievement)f

- Self-actualization (fulfillment)

Unless the top two needs are met, people don’t spend money on other things.

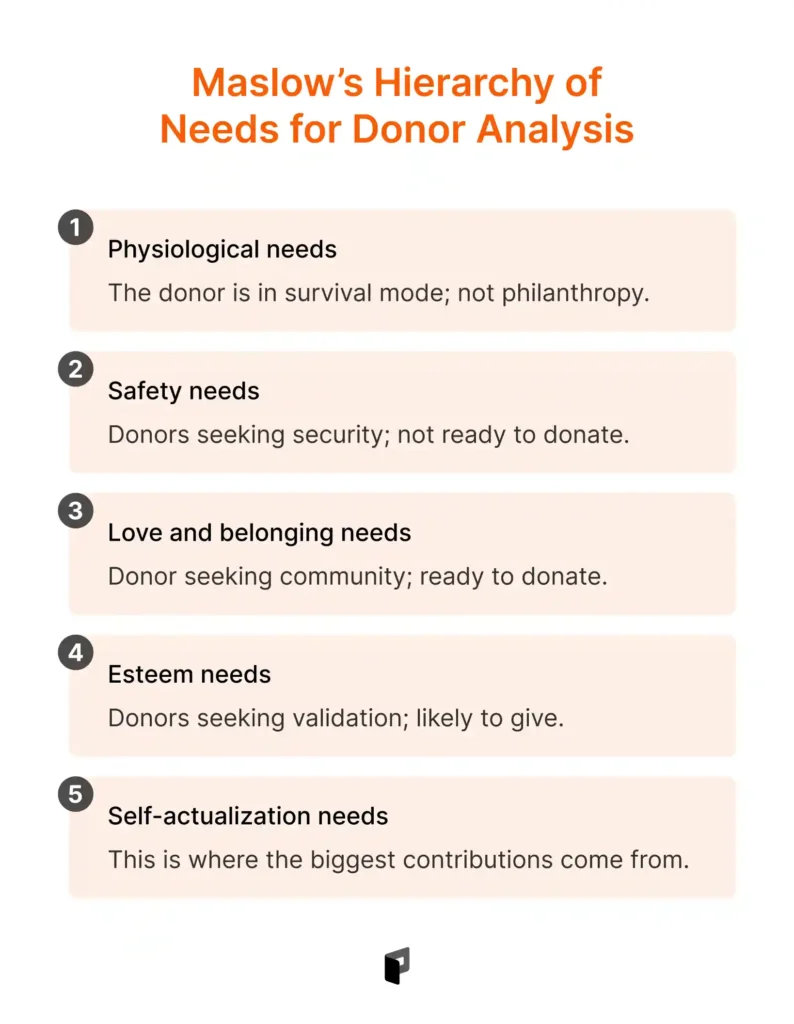

How can you relate Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to your fundraising?

It’s very important to figure out at which psychological stage your donors are –

Physiological needs

These are the most basic requirements for human survival, including air, food, water, warmth, shelter, and sleep. Don’t ask for major donations when your donor is in a crisis.

Their focus at this stage is survival. Not philanthropy.

Safety needs

Once physiological needs are met, people seek security, stability, and freedom from fear. And it includes financial stability, health, and personal protection.

Your donors need to feel financially secure and protected before they can focus on giving.

Love and belonging needs

This is the need for social connection, including friendship, intimacy, family, and a sense of belonging to groups.

This is the stage where you get donations from donors. Donations can fulfill the need to belong by connecting donors to a bigger cause or community. Your goal is to foster a sense of shared purpose among donors.

Esteem needs

This is the need for self-respect, achievement, competence, independence, and recognition or respect from others (status, prestige).

Donating to your cause should make your donors feel recognized and give them a feeling of accomplishment. By boosting the donor’s self-esteem and respect from others, you might receive good donation streams. But don’t misuse it. Or overuse it.

Self-actualization needs

This is the highest level of human need. This is the stage where people try to realize their full potential, personal growth, peak experiences, and the desire to become everything one is capable of becoming.

This is where the biggest contributions come from. Giving away to charities makes your donors feel they are building their best selves, achieving meaningful accomplishments, and leaving a legacy to follow.

Psychological factors behind donating to charity

Donor psychology is deeply embedded in human psychology. The factors that affect people to act, the same factors that affect a donor. But there are some variations in play.

Let’s look at some psychological factors behind why and how people donate.

1. The Identifiable Victim Effect (IVE)

One of the most powerful triggers in donor psychology is the Identifiable Victim Effect (IVE).

It means people are more likely to donate, and donate more, when they see one real, specific person who needs help rather than a large group described only by numbers or statistics.

This happens because donors often rely on emotions when deciding to give. Feelings like sympathy, sadness, and compassion play a bigger role than logical thinking about where money could help the most.

Psychologists call this the affect heuristic. Instead of analyzing impact, donors react to how a story makes them feel in that moment.

Even though a disaster affecting millions is objectively worse than the suffering of one individual, our brains aren’t always wired for math. They are wired for emotion.

The affect heuristic:

When we see a single face or hear a specific name, we experience the affect heuristic. This means we make a decision based on an immediate emotional reaction like sympathy or compassion rather than an analytical calculation of where our money will do the most good.

Psychic numbing:

You might think that adding statistics to a personal story would make your case stronger, but research suggests the opposite.

In a famous study by Small, Loewenstein, and Slovic (2007), donors gave nearly twice as much to the story of a single hungry girl named Rokia than they did when presented with statistics about 21 million hungry people.

Interestingly, when the story of Rokia was shown together with the statistics, donations went down compared to Rokia’s story alone.

I can say that analytical thinking can weaken emotional responses. Researchers often describe this effect as psychic numbing, where large numbers reduce emotional engagement instead of increasing it.

When donors start thinking analytically, it suppresses the emotional spark needed to give.

Singularity and unitization:

The Identifiable Victim Effect is also influenced by how donors perceive impact. People feel more motivated when they believe their donation can fully help or “solve” the problem for one person. This is called singularity.

However, later research by Smith, Faro, and Burson in 2013 found an important exception. When multiple victims are presented as a single unit, such as a family or a village, donors respond emotionally in a similar way as they do to a single individual. This idea is known as unitization.

By turning a crowd into a single entity, you help the donor feel that their contribution can truly “solve” the problem, rather than just being a drop in a vast ocean.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- Lead with a real, specific human story instead of large statistics

- Show how a single donation can make a clear and complete impact

- Limit heavy data early, since too much analysis can reduce emotional response

- If helping many people, present them as a single unit like a family or village

- Make the cause personal and easy to emotionally connect with

2. The Warm Glow Effect

You might assume that donors give to charity purely to help others. But economists and psychologists have discovered a more complex truth.

Donors also give because of how it makes them feel.

This phenomenon is known as the warm glow effect. This idea was developed by economist James Andreoni and changed how nonprofits now understand charitable giving.

According to the warm glow effect, donors are not purely selfless. Their motivation is a mix of two things. One is a genuine concern for improving a cause. The other is the personal happiness, pride, or satisfaction they feel from the act of giving itself.

In simple terms, donating creates an emotional reward. That positive feeling is like a private benefit the donor receives in return for their contribution.

Brain research supports this idea. fMRI scans reveal that when people donate money, the “ventral striatum” lights up. This is the same reward center of the brain that reacts to physical pleasures like eating delicious food or seeing a friendly face.

That means the brain treats a charitable donation like a personal reward.

One of the most fascinating proofs of this effect comes from a study by Crumpler and Grossman (2008). They designed an experiment where every dollar a participant gave was canceled out by the researchers. Means the charity received the same amount of money regardless of the participant’s choice. And the donation had no real impact on the charity’s total funds.

Yet, 57% of people still chose to give. They weren’t giving to increase the charity’s bottom line.

They were giving to purchase that internal feeling of satisfaction.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- People donate not only to help others, but also because giving feels good

- Highlight the emotional satisfaction of donating, not just the impact

- Make donors feel personally involved and appreciated to strengthen the warm glow

- Private giving can remain strong even when public or large funding exists

- Social recognition can boost giving, but it works best when donors feel connected to the community

3. Social proof and peer influence

People naturally look to others when deciding how to behave. Learning what others contribute sets a norm for donors’ behavior.

A field experiment by Jen Shang and Rachel Croson shows:

When callers were told that a previous donor had contributed a high amount, such as $300, returning donors increased their own donations by an average of 29 percent. On the other hand, when callers were told that the previous donor gave less than what they themselves had donated before, their contribution dropped by an average of $24.

Interestingly, science suggests that social proof works more through social pressure than through pure joy.

Studies using Event-Related Potentials found that hearing about higher donations from others creates a sense of social pressure rather than happiness.

This suggests that social proof often works because donors feel nudged to comply with a social norm, not because they suddenly feel more generous.

Social proof becomes even more powerful when it comes from people donors feel close to or identify with. General statements like “most people donate this amount” are less effective than messages that reference a specific group.

For example, information about what people in the same city or of the same gender donate has a stronger influence.

In one study, matching the gender of a previous donor to the current caller increased donations by 34 percent compared to when the genders did not match.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- Show donors what others are giving to set a clear reference point

- Use higher but realistic contribution examples to encourage larger donations

- Match social proof to the donor’s in-group, such as location or gender, for stronger impact

- Avoid showing lower donation amounts that could pull contributions down

- Remember that social proof works by reducing hesitation and social pressure, not by increasing generosity alone

4. Overhead cost and perception of Impact

One of the biggest psychological barriers to giving is how your donors perceive their money is being spent.

Most donors have a strong dislike for overhead costs. This is the money a charity spends on administrative costs, salaries, and rent.

A large field experiment by Gneezy and colleagues in 2014 illustrates how powerful impact perception is. The study involved about 40,000 potential donors. Researchers tested different ways to ask for money and found that when donors were told a private benefactor had already covered all overhead costs, the results were massive.

When donors were told that a private benefactor had already paid for all administrative costs, the donation rate increased by 80 percent. The total amount raised also increased by 75 percent compared to traditional approaches like seed money or matching grants.

This shows that donors are not necessarily opposed to overhead itself. They want to feel that their specific dollar goes entirely to helping beneficiaries.

Another research shows that when donors are allowed to choose how much of their donation goes toward overhead, total donations tend to increase. Having control reduces the feeling that overhead is a hidden or forced cost

However, transparency around overhead is complex. While sharing information can correct misunderstandings, it can also push donors into more analytical thinking. This can unintentionally reduce emotional connection and sympathy for the cause.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- Donors want to feel their money directly helps people, not operations

- High overhead reduces perceived impact, even if it improves effectiveness

- Messaging that reassures donors their full donation reaches beneficiaries can significantly increase giving

- Giving donors a sense of control over how funds are used can boost donations

- Be transparent, but avoid overloading donors with details that trigger too much analysis

5. The Bystander Effect

We’ve all seen it happen. A call for help goes out to a massive group, and everyone stays silent, assuming someone else will handle it.

In psychology, this is known as the Bystander Effect.

In both online and offline fundraising, this is one of the biggest problems. Each potential donor assumes that someone else will donate, so they feel less personal responsibility to donate.

Research consistently shows that as the number of people involved increases, the chance that any one person will donate goes down. In laboratory studies, individuals who were asked alone were the most likely to donate and also gave larger amounts.

This pattern continues in digital fundraising. Broad email campaigns or public crowdfunding pages often feel less urgent than direct, one-to-one requests, even if the cause is serious.

Several psychological factors support this effect. One is pluralistic ignorance, where people assume that if others are not responding, the situation may not be urgent. Another is evaluation apprehension, where donors worry about how their contribution might be judged, such as whether it is enough or appropriate.

To fight bystander apathy, the key is personalization. Even if a campaign is reaching thousands of people, individual communication makes the donor feel that their specific help is needed. This can override the urge to wait for someone else to step in.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- Large, mass appeals reduce personal responsibility and lower donation rates

- People are more likely to give when they feel personally asked, not part of a crowd

- Broad emails or public campaigns often feel less urgent than one-to-one outreach

- Emphasize individual responsibility to counter the “someone else will donate” mindset

- Personalization, even at scale, can significantly increase engagement and action

6. “Even a Penny Will Help”

Sometimes, a potential donor wants to help but feels embarrassed because they can only afford a small amount. They might worry that giving just a few dollars makes them look cheap or that their contribution won’t matter.

This is where a technique called Legitimizing Paltry Contributions (LPC) comes in.

The main idea is: By explicitly stating that even a tiny amount is welcome, you remove the social pressure on donors and the excuse of not having enough money to make a difference.

A classic field experiment by Cialdini and Schroeder in 1976 shows how powerful this approach can be. When the phrase “Even a Penny Will Help” was added to a donation request, the number of people who donated increased from 28.6% to 50%.

Also, people did not give smaller amounts because of this message. The typical donation stayed the same at one dollar in both cases.

This is incredible and one of my most favourite findings. When you make it socially acceptable to give a small amount, you don’t actually get smaller gifts. Rather, you get more donors who were previously too shy to contribute.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- Clearly say that small donations are welcome and valued

- Remove the fear of looking cheap or not giving enough

- Focus on increasing participation, not just average donation size

- More donors giving small amounts can raise more total funds

- Make donating feel easy, safe, and judgment-free

7. The Watching-Eyes Effect (social monitoring)

This finding is really interesting.

People are more likely to act generously when they feel they are being watched. This is called the Watching-Eye Effect. This phenomenon is driven by social image concerns, or the desire to look kind and generous in the eyes of others.

In a fascinating supermarket study, researchers tested how people reacted to different images on a donation collection box. When the box featured images of human eyes, donations jumped by 48% compared to when the box featured neutral images, like flowers.

Even though the eyes were just a picture, they triggered a deep-seated psychological response. The effect was strongest in quieter environments, where the eye images stood out more and were harder to ignore.

Takeaways for fundraisers

- Subtle cues that suggest visibility can increase donation amounts

- Simple elements like eye imagery can trigger generosity, even without real monitoring

- These cues work best in calm, low-distraction environments

- In digital campaigns, signals that make donors feel seen can increase how much they give

- Social image and reputation strongly influence donor behavior

Subscribe Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for updates, exclusive offers, and news you won’t miss!

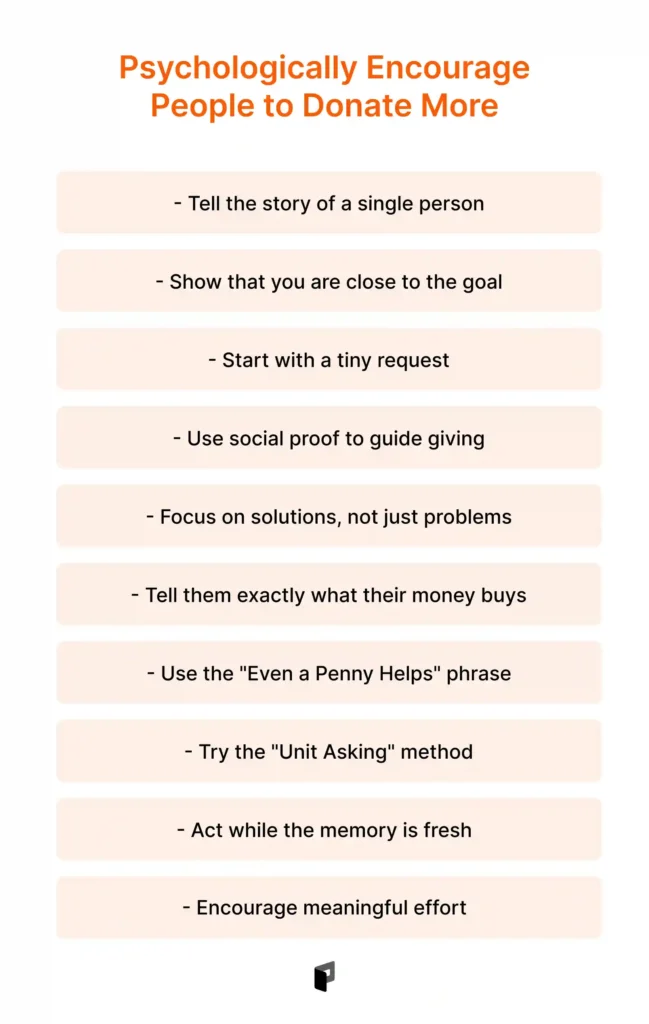

How to psychologically encourage people to donate?

Now that you know about the psychological factors that motivate or demotivate your donors, you need a strong plan to get more donations for your new or existing campaigns.

Let’s talk about some donation campaign strategies.

– Tell the story of a single person

People feel much more sympathy for one individual than for a large group. Instead of using big statistics, tell the story of one specific child or family in need.

Research shows that donors give nearly twice as much when they hear about a single hungry girl compared to when they see statistics about millions of hungry people.

That’s because large statistics can make donors feel overwhelmed or numb to the situation. On the other hand, a single face makes the problem feel real and personal.

– Show that you are close to the goal

Donors love to feel like they are the ones who helped cross the finish line. If your campaign is reaching its target, make sure to tell your supporters.

This is known as the Goal Gradient Effect, where motivation to help naturally increases as a target becomes closer.

In crowdfunding, donors are almost three times as likely to give right before a goal is reached compared to after the goal has already been met. Highlighting your remaining progress makes every small gift feel like it has a much larger impact.

– Start with a tiny request

If you want donors to make a large donation, ask them to do something small first, such as signing a petition.

Once a person agrees to a small favor, they begin to see themselves as a supporter of your cause. This changes their self-perception and makes them more likely to agree to bigger requests later. This is called the Foot in the Door technique.

One study found that 76 percent of people who agreed to a small request later agreed to a bigger one. Only 17 percent of people agreed without doing a small task first.

People naturally want to stay consistent with their past actions. So do your donors.

– Use social proof to guide giving

If potential donors see that many other people are already giving, they are more likely to join in.

Sharing a list of recent donors or mentioning what most people give sets a helpful standard for new supporters to follow. Use this wisely for your donation campaigns.

– Focus on solutions, not just problems

Focusing only on how bad a situation is can actually make people feel helpless and less likely to give. Instead, focus on how your organization provides a clear solution.

Research from Yale shows that framing a nonprofit as a source of solutions significantly increases the intent to donate. Donors respond much better to a message that says “Here is how we are solving this” than to one that only says “Look how terrible this problem is”.

When donors see a path forward, they feel more empowered to take action.

– Tell them exactly what their money buys

Studies show that donors give nearly twice as much when they clearly understand where their money goes, including simple explanations of the donation campaign and overhead costs.

Provide specific and concrete details of your fundraisers. Better if you tell them exactly what a specific amount will buy. For example, “Every $10 provides a bed net for a child in Africa”.

But don’t overstimulate your donors with all the information. Big numbers also demotivate people.

– Use the “Even a Penny Helps” phrase

Sometimes people don’t donate because they feel their small gift won’t matter. You can remove this fear by explicitly stating that even a tiny amount is welcome.

This removes the mental excuse of not being able to afford a donation.

– Try the “Unit Asking” method

If you are raising money for a large group, try asking the donor how much they would give to help just one person before asking for a donation to the whole group.

In a real fundraiser, people who were asked to help one child donated an average of $49. Those asked to help a whole group gave only $18. This small change in how the request was framed increased total donations by over 200 percent.

– Act while the memory is fresh

If someone has recently benefited from your organization, ask them for a donation quickly. The desire to give back fades fast. The sooner you ask, the more likely they are to donate.

A large study found that for every 30 days that passed after a person received service, the chance of them donating dropped by 30%. Capitalizing on that narrow “window of opportunity” is vital for your schools, hospitals, and other service-based charities.

– Encourage meaningful effort

It might seem strange, but people often feel a deeper connection to a cause when they have to work for it.

Events like charity marathons or the Ice Bucket Challenge are successful because the effort and pain involved make the contribution feel more meaningful to the donor. This is called the Martyrdom Effect.

When a cause is linked to human suffering, a donor’s personal sacrifice feels like a powerful, symbolic way to align themselves with the people they are helping.

Two more things

This article is almost over. But I wanted to talk to you about two more important factors when you are organizing a donation campaign.

1. Shift from “Guilt” to “Hope”

For a long time, many charities used “pity porn”. Sad images meant to make donors feel guilty. While guilt can get a quick, one-time donation, it often backfires. It leaves donors feeling drained, and they rarely come back.

Today, the most successful fundraisers focus on agency and hope.

Instead of showing people at their worst, show their strengths and their potential. When you highlight the resilience of the people you help, you invite donors to be part of a success story. Hope builds a long-term bond, while shame only creates a guilt gift.

2. CTA: “Donate Now” vs “Support Our Mission”

Research shows that “Donate Now” consistently outperforms abstract phrases like “Support Our Mission.”

This is because “Donate Now” is a clear, urgent command that tells the user exactly what to do next. On the other hand, “Support Our Mission” is more of a philosophical idea. It feels less urgent and doesn’t clearly define the mechanical action needed.

For fundraisers, if you want to increase your conversion rates, use direct, action-oriented language that removes any guesswork for the donor.

Conclusion

As we’ve come together to the very end of this article, we’ve established the fact that giving a donation is rarely a purely logical calculation. It is a deeply personal act driven by emotional connections, social cues.

By studying donor psychology, you do not “hack” your donors. You remove the psychological barriers that prevent your potential donors from acting on their best intentions.

As an NGO or fundraiser, your mission is far too important to be left to guesswork. People want to help, and your job is to make it easy and rewarding for them to say “yes.”

Now, take these donor psychology lessons with you, refine your storytelling, and go turn that psychological spark into a lasting flame of impact.

Thank you for reading. Hope it helps.

Join the thousands already enjoying Paymattic Pro!

Mahfuzur Rahman Nafi

Mahfuzur Rahman Nafi is a Marketing Strategist at WPManageNinja. With 4 years of experience in Product Marketing, he has developed marketing strategies, launched products, written content, and published websites for WordPress products. In his free time, he loves to read geeky stuffs.

Leave a Reply